Trigger Warning: R*pe, Inc*st

Story by Isabella Gao

Illustrated by Emilie Cooper

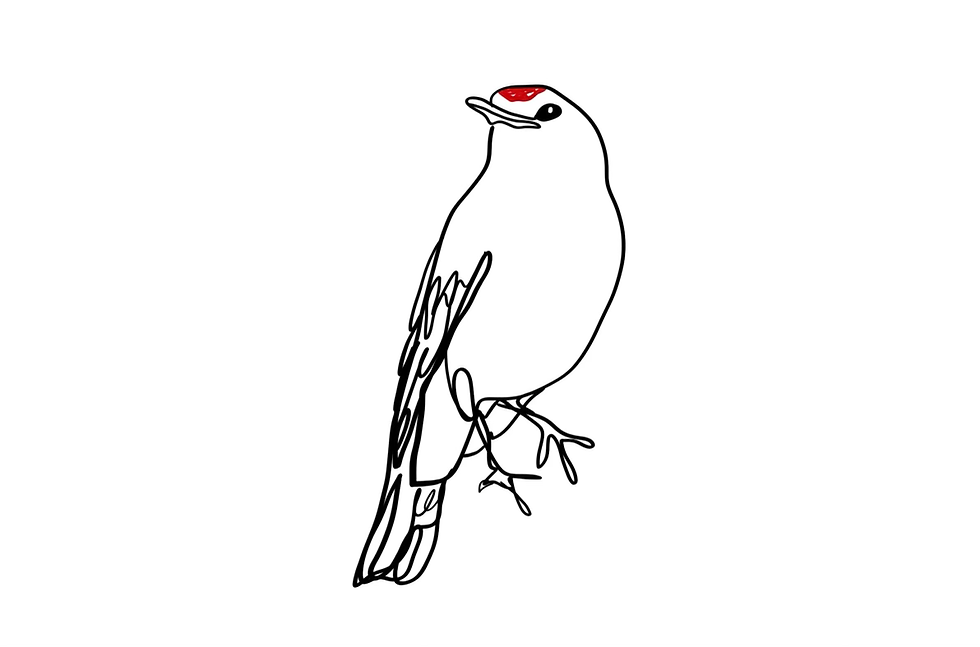

As his calloused hands pressed firmly against her neck and the faded gray-blue of his jean leg settled near her crotch, she became a Northern bird in flight. As the stained mattress creaked below her adolescent body and the low drone of Channel 5 mixed with her young cousins’ indistinguishable speech, she felt the cold-hot sting of circulating whirlwind blocks along the winter migration cycle. Though the heater churned the air in the apartment at a constant 23 Celsius, when she heard each individual tick of his zipper sliding down, the room became a Nunavut icebox. She shut her eyes so tightly her mother’s face would settle grimly if she saw the deep creases forming in ripples around them and reimagined herself as a common redpoll, body small and speckled, but with an unmistakable stroke of red around its crown. As his weight fell upon her frame, a harsh winter draft toppled her, but the soothing call of companion birds helped her to regain her balance. She visualized herself yelling out, with a high-pitched shriek, alerting all the animals belonging to the winter tundra she was fearless.

But when he finished, she became herself again every time. She limply rolled away and pulled her jeans back over her shaky legs, stepped from the room, nodded gently to her aunt and baby cousins, refused to sit for some steeped tea from the chipped green kettle, said that she was tired and needed to go home to do her homework, and shut the front door’s mesh-screen to her uncle’s house. She did this every time her father asked her to deliver his brother’s share of the excess inventory that his Asian mart had not sold that month. And as she walked under the dimmed streetlamps, the searing cold of his touch dissipated into flaming coal stones, pressing into her skin one by one. One for how her aunt did nothing when she left her uncle’s room but pull her eyebrows down and demand she take home a bag of sweets. One for how his gruff voice haunted her in quiet places: the library, the testing room at school, the glass-sheened pool when closing shift arrived. One for how she was a whore, the only girl who had not been a virgin at sixth-grade graduation. One for how her voice choked and faltered when she met her father, asking excitedly if she’d had fun at his brother’s home. Each time she wandered into the tennis courts at Haultain Park, a quarter of the way home, she screamed out all the pain. It sounded nowhere near the redpolls’ elegant chirps, forced to listen to her from their perches in the lofty trees.

“Marikina,” her mother murmured, “is the most beautiful city in the world.” When she was five, her favorite bedtime story was of the city her mother had left. She loved it when her mother traced her delicate fingers through her hair and under her chin as she recounted memories of her home, 11,000 kilometers from Calgary. “Long ago, the Spaniards came down from their giant ships and found our beautiful land. They tasted the honeyed mangoes and melons and saw the teeming coral reefs and they decided to stay. Our town was first named ‘Mariquina’ by the Spanish, then, a hundred years later, changed to ‘Marikina’ by the Americans. We continued to fight, and fight, and eventually, the Philippines was free. The Americans freed us from themselves, from the Japanese in the war, from the Spanish who came so long ago, and ‘Marikina’ became our own. This is what you must always do when they take your freedom for you. Reclaim what they called theirs and make it yours, Marikina.” She beamed under her mother’s pride and nearly felt the radiant island sun shine down on her the way it had her Filipina mother thirty years before, even though she’d never left the snowscape of Alberta Province.

Marikina, she’d whisper to herself, long after her mother had fallen asleep beside her, basking in the delight of being called a name so beautiful. She closed her eyes and smelled the humidified trees, ones which bore fruit each year faithfully, she heard the whir of the wheels below the tan-beige rickshaws, and she tasted the creamy ice of her mother’s neighborhood halo-halo stand. But only in the squarish bedroom on the second floor of their cramped apartment, did the name Marikina exist. Because her father, who had a slimmer nose, a lighter complexion, bigger eyes, and smaller lips, did not approve of his half Chinese daughter being reduced to an island Asian.

Her real name, the one that had labeled her bassinet in the Rockyview General Hospital, was Peiyang Hao. And to the white nurses and doctors who had delivered her seventeen years ago, she’d been a perfect Chinese girl, all set up for a life in tightly wound double braids, pristine white sneakers, a flexible tongue versed in Mandarin, and bright big eyes, double eyelids as the only fold in an otherwise alert, pale face. But to her father, the disappointment had been immeasurable. Peiyang’s skin was a half-shade darker than the rest of her father’s family, typically indistinguishable but glaringly present when they all stood in red on Chinese New Year, posing for another portrait that would hang in her grandfather’s hall. Peiyang could not attend school, unless she spent fifteen minutes with the bathroom door locked that morning, delicately placing eyelid tape above her natural fold, and tucking the strips back into the corner of the cabinet after blinking away the scratchiness of the shiny adhesive bands. Peiyang had fumbled while holding the ink brush during her turn to paint a character onto the Chinese School’s end-of-year poster, and had smashed the ink tablet into sharp black chunks across the schoolhouse floor, leaving the intricately carved dragon in its center fragmented and lifeless. Peiyang had struggled to pronounce her own name to her grandparents, eventually giving up upon looking to her father for encouragement and seeing embarrassment instead.

When her father had forbidden her from calling herself Marikina, she’d boldly demanded an explanation of why he had married her mother if he had been ashamed of her heritage. He’d hung his head and rubbed his hand, shaped so similarly to her uncle’s, across the back of his neck. After he recovered, he had refused to answer her, shifting calmly through the channels on their old and boxy cable television. She’d turned, about to ask her mother, and then he spoke, voice void of feeling. “Your mother was a mail-order bride.” And she’d halted, right there in the hallway, staring at the framed portrait hung up of her mother and her father, holding up their squirming baby girl. Her mother’s youthful face stared back at her, barely twenty-five, while her father’s facial creases dimmed the photo, already forty-three.

On weekend nights, from six to ten, Peiyang worked at the Inglewood Aquatic Centre. Unbeknownst to her parents, she had applied under the name Marikina, and the eight block letters printed confidently across her plastic name tag brought her a kind of joy she never felt on weekdays. Two months after she was hired, her name tag’s safety-pin closure had popped and the tag had fallen from her chest onto the slick, wet poolside floor, and when she spun around upon her realization, from the blurred cycloid of her vision, she saw it crack beneath the rubber slipper of an elderly man, who then fell backwards, gray and balding head towards the concrete. Her scream as she watched him fall was louder than the calls of the redpolls nestled behind her school building in the densely packed trees. But like a movie character, a slim boy rushed beneath him and stifled the fall, and the snap that emerged behind came from the boy, rather than that man.

Peiyang had slipped to the ground herself, heaving as her tears dripped into the shiny salty pools that lined the ground. She’d cried harder then than she had ever dared to on the walk back from her uncle’s apartment, and like the snap that came from his arm and rippled across the surface of the pool, she felt the same crack of heat explode within her chest. Her knees had scraped the floor hard and they’d tinted the water surrounding her a sheer coral, like the color of her father’s cheeks when he’d introduced her mother to their Chinese neighbors. She was almost fired that day, knees stinging with salt and blood, head low, name tag resting at the bottom of the manager's wastebasket in pieces. But as she cried inside the small office behind the main desk, Sofie had sighed, and as she stood there with her head down, a sheet of hair guarding her from the tenseness of the room, the printing machine began to whir. She’d been handed back a fresh new name tag, white and unfractured, unlike the boy’s humerus.

Peiyang later learned that she had known him almost all her life. Andrew Huang had sat in the back two rows of her IB classes since the start of secondary school. His nose was disproportionately large, propped in the center of a long face, with ears outstretched as if they aimed to compensate for how narrow it was. His body was slim, his legs not much longer than hers, and the hairs that covered his arms and legs were fine enough to miss upon first glance. He sometimes rushed through the school hallways in dripping shorts, passing by his name engraved upon a row of regional swim awards hung by the school’s sports trophy showcase. He stuttered when he spoke, and his voice had cracked twice at the winter talent show, so he’d swung his arms boisterously to make up for the shame that had crossed his face. But when she passed the Debate Club’s classroom on Tuesday afternoons, he did not stutter at all, and his voice rang loudly and clearly above the other students.

She later asked him why he had used his body to cushion that old man’s fall, and he’d grinned sheepishly without answering. A few brief moments of silence passed as he rocked on his feet, resting his blue sling atop his good arm. “I noticed your name tag says Marikina? Why?” he’d asked abruptly, interrupting the tranquil quietness that had built between them. She’d shifted on the balls of her feet nervously and had answered monotonously, displaying the lack of caring she wished she felt. “Marikina is what my mother calls me. It’s the name of the city she’s from, in the Philippines.” And the stillness that followed seared bright, like the freeze of Canadian winters. Peiyang looked up at him, unsure what she was anticipating, but what met her was not it. He’d been grinning, dimples like deep sockets of glitter, when he commented, “I think it sounds beautiful.” And for a moment, her heart warmed and pooled with the glitter of his dimples and again, she felt like a flying redpoll, but no longer airborne in anguish. Andrew Huang, whose last name punctuated China’s imperial color, whose inked characters were proudly framed in the right-wing entryway of the Chinese Alliance Church, who’d flown across the border and taken an AP Chinese exam in Washington state, had not been ashamed of her for being less than fully Chinese, or for recognizing it. Andrew had nestled, like a little bird, deep into the concavity of her mind.

That night, Peiyang’s muffled footsteps stopped at the end of the street, where the convenience store’s lights were still ablaze and hushed words floated between the sounds of the gas pumps running. She could walk home. She could step inside noiselessly, leave the bag of homemade peanut candies her aunt had baked tenderly in her countertop oven on their old oak shelf, and climb upstairs into her room. She could step inside the closet, line the gap between the sliding doors and brownish carpet with shirts, and cry. But if she did that, she didn’t know when or how she’d stop crying. She was too afraid of the anger that would light her parents’ faces to confess the truth, so she bore it, the years of bright hot worry dampening her. Or, she could forget about all of it. So she falteringly stepped away from the familiar winding path that led to Henwood Street, and towards the warmly lit yellow house that Andrew lived in, whose address he had scribbled sloppily and passed to her as they sat through French’s lecture. She clutched the bag of candy squares in front of her body, and the shiny bag crinkled repeatedly as it hit her thighs, like the soothing rhythm of a low drum beat. She stopped in the center of the street in front of his house, fifteen feet away.

“Hello?” he answered, voice offbeat through her outdated cell phone. “Can you come outside?” she asked, voice wobbling more than she’d anticipated. He hung up, and the muted beeps that tapped the night air chipped at her, slowly taking away the hope she’d had of seeing him. But a half second before she turned to walk home, his front doorknob rattled and he emerged, yellow puffer jacket zipped up to his mouth, knotty scarf wrapped haphazardly around his head. His slippers matched oddly with his heavily bundled upper half, and his socks were different lengths. But as he stumbled off the sidewalk and into the street towards her, she knew she’d never care less about his quirks. Andrew approached her cautiously, confused as to why she’d visited his house at ten pm on the railing end of winter break. “Are you alright?” he aired, tentatively walking towards her. She didn’t see the red tint of his cheeks underneath the decolorizing propane lamp. He fumbled as he took his hands out from his pockets, and he threw his threadbare maroon scarf over her head. Shocked, Peiyang dropped the bag of candy.

As it hit the ground, he took the final step forward, closing off the space between them. He kissed her, in the middle of the street, in front of his dimmed house. He abruptly pulled away a moment later, eyes wide with fear. “That was my first kiss,” he stammered. The air grew cold as the silence built in pressure. “Was it yours?” he blurted, seemingly wanting to fill the tension with words. And Peiyang fell, knees buckling, the way she had two years ago when he swooped under the old man at the pool. She cried, and her tears seeped into the black asphalt. They burned hot streaks down her cheeks for the shame she felt when Andrew wondered whether he had been her first kiss too. For how her uncle had shoved his stifling tongue into her mouth and she had choked at her family’s Mid-Autumn Festival party six years earlier. And she finally sputtered out the words she’d never said to anyone since it started. “My uncle rapes me every month.”

And Andrew stood above her, head faced straight forward, and for an instant, the darkened expression on his young Chinese face mirrored that of her uncle’s weathered Chinese face. And as Peiyang pressed her palms into the pockmarked blacktop beneath her to back away from him, his expression snapped like his arm had when they were fifteen. And tears began to drip down his face, something that she’d been surprised had never happened that day at the pool. His next words came out as a coarse whisper, “So that’s why you’ve always acted funny.” He stared directly at her, eyes pooled like blackened, moonlit water. His voice broke with his next word. “Marikina.”

He set himself onto the ground gently, sideways to her right, on the dark pavement. She pulled her knees up to her face because she didn't want him to touch her again. Because when he did, it felt so similar to her uncle that the feeling marched across her skin like a desert fire. Because she could never be touched by a Chinese man again without that familiar fear breaking through her like luminance scorched through a cracked glowstick. Because Andrew deserved to love a girl who was not a whore. Because she feared he would say the words her parents had said when the local assault case had crossed their television screen last fall - that after three years she would not remember what he’d done and then she’d realize how superfluous the humiliation she’d drawn to her family had been. Because she’d never had a chance to touch somebody out of desire instead of fear. She held her breath, waiting, but Andrew didn’t say a single word to her for the rest of that night. Instead, he stood up slowly, picked the crumpled bag off the ground, and nodded towards her as he turned back to his house. His dimples had shown in his grimace, and they were no longer lined in lustre. Those peanutty sweets sat uneaten and unopened on his kitchen counter for three months, until they were thrown into the garbage by his brother.

Marikina sat outside for a long time, until the moon disappeared behind gray clouds and her father’s rings died along with her phone’s battery. And she closed her eyes again, envisioning herself as that brave redpoll, soaring through bitter winter skies. But maybe as that redpoll circled the hazy whiteness of the Arctic Circle, it had died, leaving its lover chirping like a smoke alarm, waiting.